Originally Posted on Slate.com

Evan Spiegel, Snap’s 27-year-old CEO, isn’t in the habit of explaining himself to the public. Until recently, he rarely had to: Snapchat’s wild popularity, especially with teens, spoke for him. The eight months since Snap went public, however, have seen the company’s best ideas widely copied, its stock tumble, and influential users defect to rival platforms. All of which has forced Spiegel’s hand. On earnings calls and in media interviews, the former enfant terrible has begun trying to tell his company’s story and articulate its vision to an audience that has always struggled to understand it: adults.

That story and vision are interesting not only for what they say about social media, but for what they tell us about the relationship between data, intuition, and creativity in a 21st-century technology company. They tell us that you don’t have to obsessively optimize and crunch numbers like Facebook or Google to build an app that people love. But you just might have to do it if you want to compete with them effectively as a public company.

On the surface, Snap might look like your stereotypical Silicon Valley get-rich-quick story. Three brash dudes in a dorm room hacked together a seemingly frivolous app; it caught fire with the kids; six years later, it’s a $20 billion company rewriting the rules of media, publishing, privacy, and online interaction.

But listening to Spiegel talk about Snap suggests another way of looking at it—one that sets it apart from its Silicon Valley rivals and holds it in opposition to prevailing winds in technology and industry. He justifies the company’s decision-making by appealing to theory, intuition, and anecdotal observation rather than empirical data. He portrays its sometimes confounding interface as the product of conscious design decisions that prioritize creativity and self-expression. And he explicitly rejects the notion that machine-learning algorithms can replace human editorial judgment.

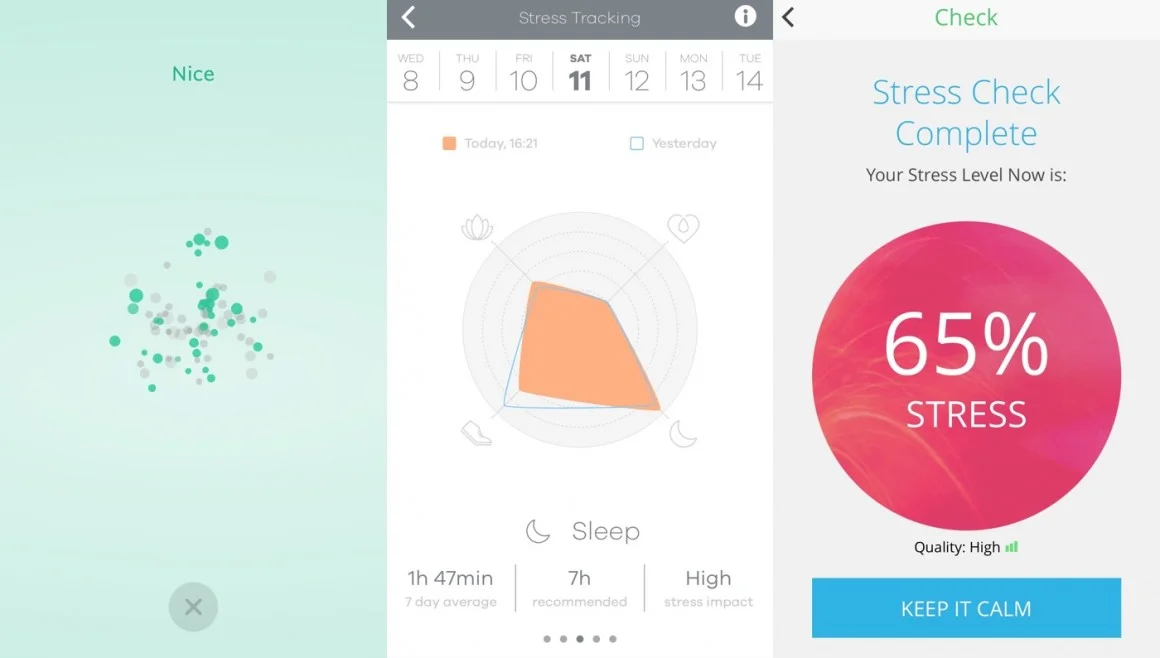

In a time of ubiquitous rankings, ratings, and likes—when Google ranks search results; Facebook ranks your friends’ posts; Uber and Airbnb rate drivers, riders, hosts, and guests; Yelp rates businesses; and Amazon rates products—Snap’s success speaks to a backlash against the quantification of everything. In the most generous interpretation, it represents a triumph of human intuition, creativity, and whimsy over spreadsheets and algorithms. Less charitably, it might be seen as a victory for flying by the seat of one’s pants.

The good news for Snapchat is that teens love it more than ever. A Piper Jaffray survey released Saturday found that 47 percent of teens named Snapchat as their favorite app. That’s more than Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter combined. Yet one of Facebook’s Snapchat clones, Instagram Stories, needed less than a year to surpass Snapchat in active users. And a recent marketing study of 12 top “influencers” active on both platforms found that they were posting more to Instagram and less to Snapchat.

The question now, with Facebook’s social media empire targeting Snap for destruction, is whether that approach will prove sustainable—or whether Snapchat’s embrace of intuition will disappear as quickly as one of its messages.

That doesn’t mean Snapchat eschews data altogether. But it seems to employ a different process than many of its Silicon Valley peers. Facebook’s news feed ranking team spends most of its time analyzing the data its users generate, looking for trends that suggest a need to tweak the algorithm. But Snapchat seems more often to start from a hypothesis, then seek data that could help to confirm or modify it.

For instance, Spiegel told Isaacson that when he started the company, 1 out of every 10 messages that people were sending on their smartphones was an image. That supported his theory that people might like a messaging service that was built around the camera, rather than around text. It also suggested that people were increasingly using smartphone pictures as a form of ephemeral, interpersonal communication, rather than to document their lives. But it’s not the sort of data point you’d even know to look for unless you first set out to rethink mobile image sharing.

Likewise, the company famously pioneered the vertical video format for ads in 2015, bucking the industry wisdom that videos had to be horizontal. Since almost no one was doing vertical videos, Snapchat couldn’t draw on extensive empirical data to prove that they would work. Instead, Spiegel told Adweek, the decision was based on the company’s own observations of how users interacted with its app. “People just don’t rotate their phones,” he said. Only after Snapchat began using vertical videos did the data exist to vindicate the move. (Other companies have since followed.)